Using Questions to Diagnose and Improve Learning

- Stewart Learning Center

- Oct 30, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 2, 2023

An adapted excerpt from Chapter 8 of Teaching Strategies That Create Assessment-Literate Learners by Anita Stewart McCafferty and Jeff Beaudry, Corwin, 2018.

Madeline Hunter included checking for understanding in her lesson plan frame more than half a century ago, so the concept of checking in on student’s progress is not a new one. Educators have traditionally used a variety of techniques and tools, but none is used more regardless of format than questioning. In today’s digital world, there are a variety of tools and resources that teachers can use to help them ask questions of their students: to gather, to sort, and to display the data in an effort to ensure that they sample all students in an anonymous, sensitive manner. A plethora of apps and tech sites have been developed to capitalize on our need to check our students’ understandings and diagnose learners’ needs. Many of our educator friends rely on Google Classroom, Google Forms, Kahoot!, Quizziz, Plickers, Poll Everywhere, QR codes, Quizlet, Socrative, Vocaroo, VoiceThread, or clicker devices. And the list goes on with a host of low-tech options like individual mini-whiteboards, traffic lights, signal response such as thumbs-up, fist to five, stand and be counted, class discussions, jot or sketch an answer, and so on.

No matter how glitzy and how engaging the questioning tool or app might be for students, a teacher’s information will only be as good as the question (stem), prompt, and/or distractors provided to students. We love the notion that the word question derives from the root word quest, which is a journey. When we pose the right questions to our students—or better yet, teach them to pose thought-provoking questions of one another—we embark upon a journey of discovery (Thoughtful Classroom, 2010). When we check in on our

students’ progress toward learning important content and skills, we must carefully prepare the questions that will allow us to determine their needs for next steps. Chappuis (2012, 2015) posited that there are three key learner needs our check-ins should help us and our learners uncover: (1) partial understandings, (2) flaws in reasoning, and (3) misconceptions. Without first identifying typical misunderstandings, reasoning flaws, or misconceptions associated with our units of study, we have little hope that our questioning in the moment will help us appropriately diagnose learner needs.

Creating hinge questions, as Dylan Wiliam calls them, at those critical junctures in the learn- ing help a teacher determine if the students understand the concept or skill well enough to move on to the next chunk of learning, need a brief recap of the lesson, need more practice time, or perhaps need reteaching. Wiliam reminds us that these hinge questions should be rapid response items where students can respond to them quickly and teachers can review responses quickly. Without carefully planning, administering, and analyzing results from questions posed at critical junctures in the learning, we often further confuse students or waste time with subsequent learning activities because students were missing prerequisite understandings or skill sets in order to be successful.

Using Questions to Diagnose and Improve Student Learning

Essential Questions to Consider

How can I better use varied effective questioning techniques to enhance student learning and diagnose learning needs effectively and efficiently?

How can I help students develop more thoughtful, well-developed, and deeper responses?

Percentagewise, questioning is one of the strategies most frequently used by teachers; in fact, most studies on the topic say that teachers spend upward of sixty percent of their instructional time asking questions, listening to answers, and providing feedback to students about their responses. Questioning has great potential when done well to greatly improve student learning and engagement. In addition to positively influencing student achievement, it also is positively connected with student success, motivation, and retention. Unfortunately, research shows that when done poorly, questioning has little effect beyond determining that a few students can recall or regurgitate key points from the lesson or unit of study.

Why Use Questioning? Teachers use questioning in order to do the following:

Engage learners in the lesson

Strengthen motivation

Promote recall of previously taught, and hopefully learned, material

Assess student comprehension

Help students make connections

Activate prior background knowledge

Develop thinking skills

Increase students’ depth of knowledge

What Does the Research Say About Questioning? A host of researchers (e.g., Brualdi, 1998; Cotton, 1988; Dantonio, 2001; Dickman, 2009; Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock, 2001; Silver, Jackson, & Moirao, 2011; Silver, Strong, & Perinni, 2003; Wilen & Clegg, 1986) indicate the following about questioning:

Effective questioning is positively correlated with higher achievement among students.

On average, teachers ask forty questions per forty-five-minute class period.

Seventy-five percent to eighty percent of questions asked are at the recall or procedure level.

Most teachers call on students perceived as higher achievers more frequently than they call on low achievers.

Teachers typically wait one second or less for students to respond to questions.

Often when a student does not immediately give a correct response, the teacher answers the question herself or himself.

On average, students ask less than five percent of the questions asked in the typical classroom.

Students who regularly ask and answer questions in class do better academically than those who do not.

A few carefully prepared and selected questions throughout a lesson have a greater effect on student learning than asking many questions (especially for learning anything beyond recall).

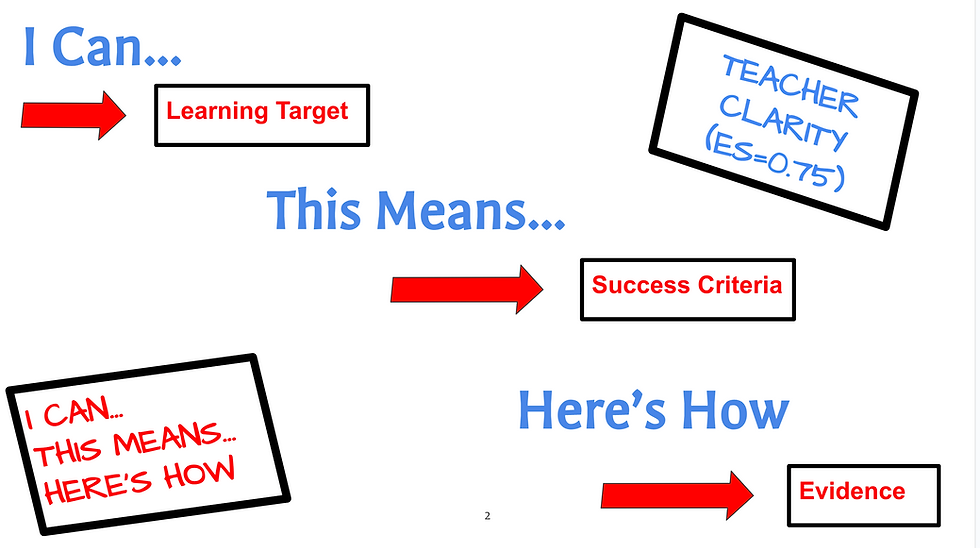

What Can I Do to Improve My Questioning Skills, You Might Ask? As the research suggests, plan a few well-designed questions to elicit higher-order thinking or complex reasoning skills as well as to meet varied learning needs. When coupled with strong student-teacher relationships and appropriate sampling strategies, questioning has the potential to vastly improve student learning. Purposefully plan questions that ask students to engage in different ways of thinking about a concept or skill improving engagement by a wider majority of students. See Figure 8.3 for an example of questions or prompts considering different ways learners may prefer to process and express their learning and associated high-impact strategies with each type of learning or thinking process. The idea behind posing these types of questions or prompts is not to pigeonhole learners into learning preferences but instead is used as a way to invite all students into the learning process and to value different ways of processing and expressing learning. Research from Thoughtful Classroom (2010) argued that teachers most often ask mastery questions (those questions that ask what, who, when, and where) and leave out other ways of processing and thinking about information—that is, the understanding learner, the interpersonal learner, and the self-expressive learner.

For too long, our classrooms have promoted and elevated one way of thinking and knowing over others, leaving many of our students feeling dumb, devalued, disrespected, and disengaged. The questions and prompts we pose—and the way we sample students—can either infuse our learning environment with new voices and ideas or stagnate the learning environment with few voices restating what teachers and texts have told them.

In addition to planning questions to engage various types of thinking, increase your think time, include more turn and talk, ask students to jot a note to one’s self, and make use of simple cooperative learning structures. Be sure you do not rely on sampling volunteers only. Develop sampling strategies that include cold calls (when appropriate), asking students to expand upon other students’ answers or justify their own responses, and/or signal if they agree or disagree with a classmate’s response with an explanation of their reasoning. Exit tickets, online random sampling generators, and the use of QR codes for differentiating questions are all additional ways to increase student engagement.

As educators, we make instructional decisions from the information we receive from our learners about next steps to take. When the feedback we gather comes from inappropriate sampling strategies or poorly constructed questions, we are bound to draw faulty conclusions about our students’ learning and what the next steps should be to help our learners’ progress. We have experienced firsthand checks for understanding that result in sampling only a small portion of our learners and assuming that the class as a whole is in good shape to move on or that all the misconceptions have been addressed by those we have sampled. We, too, have used the prompts “Any questions?” or “Is everyone all set?” often enough to know how easy it is to trick ourselves into thinking we have checked for understanding and students are ready to move on in their learning. When we teach to the “class as a whole” and not to our learners as individuals, we settle for determining that many, if not most, students seem ready for the next chunk of learning. The amount of content to cover is overwhelming, and the pressure to teach as fast as possible is real for many of us. But if we want to go far, we have to slow down and ensure that the information we gather accurately appraises students’ learning needs and helps us and them take appropriate next steps to either deepen their understandings, dislodge misconceptions, or right flawed reasoning.

Happy Questioning!

Keep Learning at the Center,

:)Anita

Comments